CSRC Blog: "Latina Lesbian Lineages: Community, Care, and Curation"

By Jocelyne Sanchez

Archivists see past, present, and future simultaneously. They understand that history is created by fact[1] and in the Western canon, fact is constructed by documentation. Archivists look at the contemporary landscape and can visualize the lineages that influenced it. In turn, they understand how the present inevitably links to the future and becomes historical fact[2]. Consequently, gaps in archives reveal not the singular decisions of individual archivists, but what society at large decides is worthy of preservation. This common practice across Western sites of knowledge production has created archival silences[3] around the histories of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people at the margins of society. Institutional marginalization is felt intensely by LGBTQ+ people and in particular by women and femmes of color within these communities.

Despite institutional barriers, LGBTQ+ people have always taken care of one another, and LGBTQ+ archivists have taken care of these histories. The work of lesbian activist, archivist, and herstorian Yolanda Retter is proof of such care. In an interview with Herndon L. Davis found in the Yolanda Retter Papers housed at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library, Retter describes her life’s work; “I’ve worked in the lesbian and women’s movement since 1971, in lesbian of color groups since 1979 and for lesbian history and visibility since 1994.” From 2003-2007, Yolanda Retter served as the head librarian of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center Library. Describing her work during these years, Retter stated, “I’m on a mission to preserve and to make accessible the history of marginalized groups. The Chicano Studies library is not specific to LGBT, but is specific to people of color. Over time, women and LGBT have not been as actively included but this is changing.” Under her stewardship, the center acquired various LGBTQ+ entries, including the archival collections of Laura Aguilar and Cyclona.

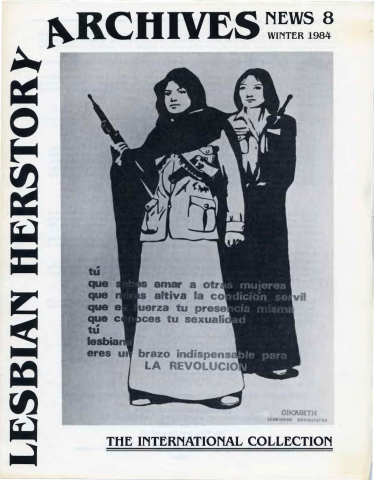

A 1984 Lesbian Herstory Archives Newsletter found in the Yolanda Retter Papers, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library.

Sixteen years after her passing, I am working on processing Yolanda’s own materials as part of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center’s Latina Futures, 2050 Lab. The various roles Yolanda Retter held throughout her life make processing her materials a riveting, fun, complex, and at times meta experience. In particular, her role as archivist makes it difficult to discern whether certain materials were acquisitions made on behalf of an institutional archive or if they are from her personal projects. Many scholars are used to seeing archival material divided into neat boxes with clear subjects, time periods, and a finding aid to help navigate it all. Unprocessed material however holds none of this information clearly.

When beginning the exploratory phase of sifting through her material, I chose my guiding point to be discovering who Yolanda Retter was. If my goal was to explore who Yolanda was, beyond just her role as a librarian, then it made perfect sense for her unprocessed collection to be nonlinear. Without preconceived expectations on what an archivist’s materials should look like (tidy, standardized, and organized), the lack of structure shifts from befuddling to mirroring a conversation. It chaotically covered multiple things at once. Sometimes jumping from one topic to another lacked cohesion, but just like a conversation with a close friend, it was fun. I was speaking with Yolanda the activist, Yolanda the archivist, Yolanda the poet, and everything in between.

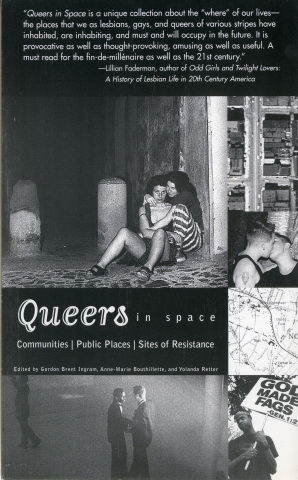

A postcard promoting a panel discussion on Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance, a book edited by Yolanda Retter, Gordon Brent Ingram, and Anne-Marie Bouthillette. Yolanda Retter Papers, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library.

Across various jobs, loves, and lives, Yolanda Retter collected lesbian history. She was both creator and curator. Just one of her boxes contains materials ranging from her lesbian magazine writing, dissertation research, acquisition paperwork, and LGBTQ+ print publications. In one place, works produced by her and works of others she collected converge. Spread throughout 50 boxes lay the various pieces of her Lesbian Oral History Project, which includes flyers, email correspondence, notes, partial transcripts, and audio-visual materials. Yolanda Retter’s passion for lesbian history shines in these oral histories. This project was a labor of love, one which she dedicated years of her life to.

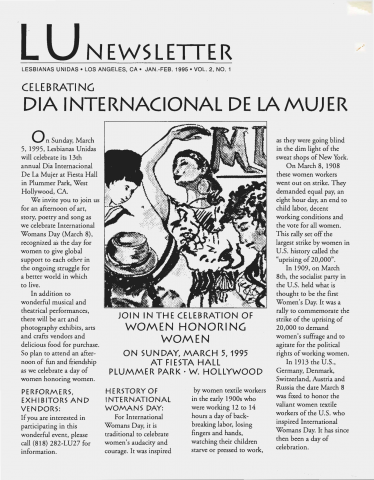

Archives that emerge from care manifest as conversations with community. Many of the Lesbian Oral History Project interviews were conducted by Yolanda, but without community support the project would not have been possible. Some of the documentation I found shows that the initial call for submissions was posted in a Lesbianas Unidas (LU) newsletter. In it, LU announced that funding for the Lesbian Oral History Project came from Latino/a Lesbian and Gay Organization (LLEGO), a national effort from Washington, D.C. Though the project was spearheaded by Yolanda, it was the collaborative nature of her archival work that made the project visible and ultimately culminated in the recording of 40+ tapes with dates ranging from the 1990s to the early 2000s.

A 1995 Lesbianas Unidas Newsletter. Yolanda Retter Papers, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library.

The Lesbian Oral History Project gives insight into the personal lives of various lesbian women. Their stories paint a picture of the changing landscape of lesbian communities throughout the decades, intertwining their personal narratives directly with wider community culture, events, and issues. Through stories of lesbian love and lesbian heartbreak, you can learn of intra-community conflicts, lesbian housing networks in the 1970s, and the development of women’s centers, showing that in the same way the personal is political, so is the archival.

At the present moment, not all of Yolanda’s boxes have been examined. As I continue to process material and uncover these histories, I find that conclusions are in constant flux, changing the context of previous findings in real time. Despite this deep dive into the life of Yolanda Retter, and the transcendent understanding and mentorship I gained through her collection, her physical absence is especially noticeable. In the archiving process, this absence is most visible when donors aren’t here to help us navigate or contextualize their materials. That is perhaps the dichotomy of archives, they preserve fragments of our work, passions, and loves, a tiny capsule of a long complex life, both connecting us to something that is gone while reminding us of its loss. Even though the grief and challenges are felt both personally and professionally, creating and interacting with archives as a community is vital to cementing LGBTQ+ elders into our collective cultural memory, allowing them to live and feed into the work long after they have left this earth.

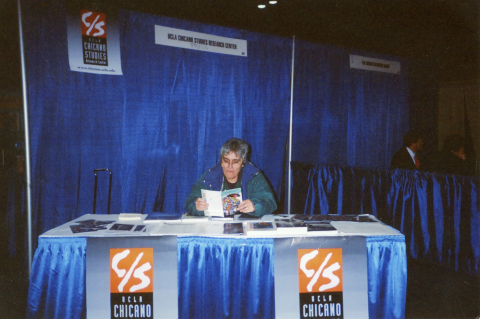

Yolanda Retter tabling on behalf of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. Date and photographer are unknown. Yolanda Retter Papers, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library.

Yolanda Retter’s commitments were first and foremost to her lesbian community. She often leveraged her professional positions in order to properly collect, record, and curate lesbian and queer histories. Her principled approach is one I seek to emulate. In processing Yolanda’s collection, I am contributing to a lineage of LGBTQ+ archival care. I honor her commitment to lesbian and queer histories by making the materials accessible via the Chicano Studies Research Center Library. I honor her truth by accepting that although navigating formal institutions and all their internal politics can be challenging, it is always possible to care for our communities and their histories.

When this collection is fully processed, I hope that you all have the opportunity to converse with Yolanda Retter and the lesbian and queer women in her collection. That when you flip through the collection’s folders and pages, you hear voices whisper back. And that as you move forward toward a liberated queer future, you feel accompanied by all the lesbian and queer people that came before you.

Jocelyne Sanchez (she/her/hers) is a recent graduate of the UCLA Masters in Library and Information Science program. She is currently the Project Archivist at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library and has spent the last months processing and researching the materials of Latina Lesbians and Chicano religious collections.

This post is part of the Latina Futures 2050 Lab, research project based at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

[1] In the chapter “The Historian and His Facts” of the book What is History, Edward Hallett Carr defines a fact as the “raw material that is available to all historians” (11) . Examples of this include dates and locations of events. Carr clarifies that raw materials are found in documents and are not in themselves history.

[2] Carr explains that a fact becomes a historical fact when it has been given validity by multiple historians (12). Validity is gained through the citing of the fact in footnotes, texts, and books, cementing it into the historical canon over the course of decades. Ultimately, it is the historian’s selection, arrangement, interpretation, and validation that creates a historical fact.

[3] The Society of American Archivists’ Dictionary of Archives Terminology defines archival silences as “a gap in the historical record resulting from the unintentional or purposeful absence or distortion of documentation”. Similar to Carr’s explanation of the historian, the archivist too plays a role in the history formation process. It is the archivist’s selection, preservation, and arrangement of documents which compile the raw materials that are available to the historian. In this manner, the selection of collections and documentation in archives determines what is privileged as history and what is forgotten.