Aztlán Spotlight Article

Toward a Mariposa Consciousness: Reimagining Queer Chicano and Latino Identities

by Daniel Enrique Pérez

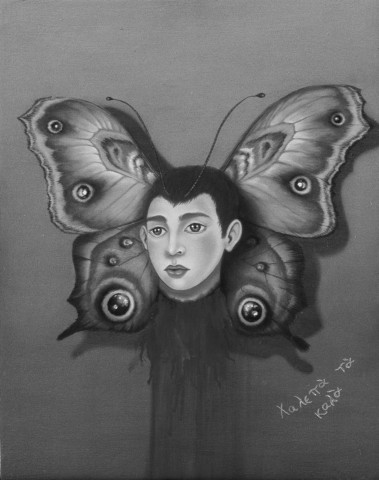

ABSTRACT: The representation of queer Chicanos and Latinos in cultural production has historically centered on negative stereotypes, depicting them as sick, passive, or hopeless, as psychopaths or victims of psychopaths, as tragic figures, or as comic relief. Nevertheless, a number of artists and writers have reconfigured queer Chicano and Latino identities by creating images that contest such stereotypes and by reclaiming and resignifying terms that have been used to denigrate these subjects, such as maricón, joto, and mariposa. This essay examines the use of butterfly iconography in cultural texts to demonstrate how butterflies as metaphors for queer Chicanos and Latinos—or mariposas—can facilitate a mariposa consciousness, a decolonial site grounded in an awareness of the social location, social relations, and history of the mariposa subject. An examination of the works of writer Rigoberto González and artist Tino Rodríguez shows how butterflies can be used to reimagine identities in innovative and positive social locations. Such sites function as discursive spaces where queer Chicanos and Latinos can overcome the multiple forms of oppression that shape their subjectivities: patriarchy, homophobia, and racism.

Mariposas in the Borderlands

Links between human beings and animals have been forged throughout history and across cultures. The relationship between the two is represented in a wide array of cultural texts, from ancient pictorial narratives to contemporary written or visual texts, and animals have often served as metaphors for human beings and human behavior. Animals are also frequently employed as semiotic devices to signify human sexuality or genitalia, as well as to delineate gender variances. In “Queer Ducks, Puerto Rican Patos, and Jewish-American Feygelekh: Birds and the Cultural Representation of Homosexuality,” Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes focuses on bird metaphors associated with queer gender and sexuality in Puerto Rican and other cultures: pato/a, pájaro/a, and feygele. He argues that these terms have historically been used in pejorative contexts to describe effeminate and homosexual males; he also demonstrates how they are often reappropriated and transformed by the subjects they were intended to marginalize (2007, 194). With respect to pato/a, pájaro/a, mariposa, and mariquita—all terms historically used as epithets to describe queer males in several Hispanic cultures—he identifies an important link with similar terms in other languages and cultures: “all of these animal words refer to insects or birds that have wings and fly, associating their use to terms in other languages such as fairy in English and feygele in Yiddish” (200).

Here, I will focus on the term mariposa, which is commonly used to describe Hispanic males who engage in non-heteronormative gender and sexual behavior, with an emphasis on attributes typically associated with femininity. I am especially interested in examining the way butterfly imagery is employed and reappropriated as a metaphor for non-heteronormative gender and sexuality. Such uses contest the traditional use of the term mariposa as an epithet and help construct alternative modes of seeing gender and sexuality. In “The Latin Phallus,” Ilan Stavans includes mariposa in a lengthy list of terms that have historically been used to stigmatize gay men in the Hispanic world and points out that gay men were typically considered “oversensitive, vulnerable, unproved in the art of daily survival” (1996, 155). Moreover, early depictions of gay Chicanos in literature were largely negative or peripheral. According to Karl J. Reinhardt, such representations can be placed into one of three categories: (a) incidental gay characters not pertinent to the plot who are presented derogatorily and who are virtually asexual, (b) gay characters somehow pertinent to the plot who commit unacceptable acts and suffer retribution, and (c) gay Chicano characters who do not participate in a Chicano space (1981, 47).

Tino Rodríguez, Beauty Is Harsh, 1996. Oil on wooden panel, 5 x 7 inches. © 1996 by Tino Rodríguez; reproduced by permission of the artist.

Daniel Enrique Pérez is a fierce mariposa warrior and Jotería studies scholar. He is the author of Rethinking Chicana/o and Latina/o Popular Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). He was born in Texas to a migrant farmworking family and raised in the onion fields outside of Phoenix, Arizona. He obtained his PhD from Arizona State University and is currently an associate professor at the University of Nevada, Reno.

To order this issue of Aztlán: The Journal of Chicano Studies, contact support@chicano.ucla.edu. To download the Table of Contents and Editor's Commentary for free, click here.